Tuesday, 10 May 2011

Chapter Eight

THE ABBEY SITE AND BUILDINGS

Place-names and documentary evidence testify to the formerly wooded nature of the Meerbrook valley. The name Leekfrith, which applies to the whole district between Leek and Meerbrook, derives from the Old English word frith, meaning wooded, and the Domesday entry for Leek mentions woods "four leagues in length and as many in breadth”. i.e. about thirty square miles. [1] The abbey was built on the north side of the flat-bottomed Churnet valley, below the lower slopes of the hill which recalls the wooded nature of the area Hillswood. Though fairly close to Leek, Dieulacres lay on the far side of the river, while on the south side another ridge and valley put it out of sight of the town.

Monastic sites were generally chosen with care, the availability of fresh water being a governing factor. It has often been said that the Cistercians in particular built their abbeys around their water-supply and drainage. The river Churnet ñowed nearby; a wellworn channel still carries fresh water from Hillswood towards the abbey site, and further to the northeast another stream supplied they abbey’s fish-pond, the site of which is marked on the 1967 O.S. (1:2500) map. A well, probably dating from medieval times, lies at the edge of the copse behind Abbey Farm, a hundred yards or so from the ruins. There was also an abundance of building materials to hand, sandstone and gritstone, and there is evidence of quarrying having taken place in the Abbey Green area and on Hillswood.

Our information about the abbey buildings rests on seemingly slender sources: a doubtful reference in the fourteenth-century Chronicle of Henry of Knighton, the Dissolution inventory of 1538, a report on the ruins which appeared in Gentleman ’s Magazine vol. 89 part I (1819), a partial plan of e. 1818 in Sleigh’s Leek, and largescale Ordnance Survey maps, 1899-1967. It is nevertheless possible to reach some conclusions as to the nature and extent of the monastic buildings, and, bearing in mind that Cistercian abbeys were roughly similar in plan and design, some gaps can be filled by comparison with better-preserved sites such as Bindon, Buildwas, Cleeve and Croxden which are representative of the middle-sized Cistercian abbey.

The original buildings at Dieulacres were started in about 1214. The Gentleman ’s Magazine report of 1819, mentions sculptured stones being found in the rubble in-filling of the church walls, suggesting that the Church was altered, if not completely rebuilt, at a later date. An entry in the Chronicle of Henry of Knighton refers to a visit of Edward the Black Prince to “Dewleucres” in 1353. Seeing the “wonderful structure (míram structuram) of the church which good king Edward had begun", he gave 500 marks (£333 6s. 8d.) towards its completion. [2] This extract raises problems, the first of which is the identity of “good king Edward”. One can almost certainly rule out Edward II! This leaves us with either the Black Prince’s father, Edward III, or his greatgrandfather, Edward I (1272-1307). Given the king’s connection with Dieulacres as its patron following Henry III’s

annexation of the Earldom of Chester, it is tempting to take Knighton’s words at their face value; the style of the pillars of the church at Dieulacres indicating the late thirteenth century (i.e. Edward I) rather than the mid-fourteenth, although some of the fragments of sculpture on the site are definitely fourteenth-century. In his original work, the present writer accepted Knighton’s statement and concluded that a new church was begun at Dieulacres by Edward III and completed by the Black Prince in the 1350s.[3] It is, however, more likely that Knighton made a mistake: he confused Dieulacres with Vale Royal, the great Cheshire abbey which was indeed begun by Edward I who intended it to be the grandest Cistercian abbey in England - mira structura without doubt. Vale Royal was certainly given 500 marks by the Black Prince in 1353 for the express purpose of completing Edward I’s church. [4] The Cheshire Chamberlains accounts show that it was paid in four annual amounts of £83 6s. 8d. [5] By contrast, there is no supporting evidence for a similar grant to Dieulacres either in the Charnberlains` accounts or in the Black Prince’s Register, nor is there any trace in the Pipe Rolls of building at Dieulacres financed by Edward I or Edward III. Royal benefactions were not normally kept hidden under a bushel: if the Black Prince gave 500 marks to Dieulacres as well as to Vale Royal one would expect to find some first-hand evidence of it. The coincidence is really too remarkable to be acceptable, and one has to conclude, however regretfully, that Knighton mistook Dieulacres for Vale Royal, and that the church at Dieulacres was not rebuilt by its royal patrons.

Our information about the abbey buildings rests on seemingly slender sources: a doubtful reference in the fourteenth-century Chronicle of Henry of Knighton, the Dissolution inventory of 1538, a report on the ruins which appeared in Gentleman ’s Magazine vol. 89 part I (1819), a partial plan of e. 1818 in Sleigh’s Leek, and largescale Ordnance Survey maps, 1899-1967. It is nevertheless possible to reach some conclusions as to the nature and extent of the monastic buildings, and, bearing in mind that Cistercian abbeys were roughly similar in plan and design, some gaps can be filled by comparison with better-preserved sites such as Bindon, Buildwas, Cleeve and Croxden which are representative of the middle-sized Cistercian abbey.

The original buildings at Dieulacres were started in about 1214. The Gentleman ’s Magazine report of 1819, mentions sculptured stones being found in the rubble in-filling of the church walls, suggesting that the Church was altered, if not completely rebuilt, at a later date. An entry in the Chronicle of Henry of Knighton refers to a visit of Edward the Black Prince to “Dewleucres” in 1353. Seeing the “wonderful structure (míram structuram) of the church which good king Edward had begun", he gave 500 marks (£333 6s. 8d.) towards its completion. [2] This extract raises problems, the first of which is the identity of “good king Edward”. One can almost certainly rule out Edward II! This leaves us with either the Black Prince’s father, Edward III, or his greatgrandfather, Edward I (1272-1307). Given the king’s connection with Dieulacres as its patron following Henry III’s

annexation of the Earldom of Chester, it is tempting to take Knighton’s words at their face value; the style of the pillars of the church at Dieulacres indicating the late thirteenth century (i.e. Edward I) rather than the mid-fourteenth, although some of the fragments of sculpture on the site are definitely fourteenth-century. In his original work, the present writer accepted Knighton’s statement and concluded that a new church was begun at Dieulacres by Edward III and completed by the Black Prince in the 1350s.[3] It is, however, more likely that Knighton made a mistake: he confused Dieulacres with Vale Royal, the great Cheshire abbey which was indeed begun by Edward I who intended it to be the grandest Cistercian abbey in England - mira structura without doubt. Vale Royal was certainly given 500 marks by the Black Prince in 1353 for the express purpose of completing Edward I’s church. [4] The Cheshire Chamberlains accounts show that it was paid in four annual amounts of £83 6s. 8d. [5] By contrast, there is no supporting evidence for a similar grant to Dieulacres either in the Charnberlains` accounts or in the Black Prince’s Register, nor is there any trace in the Pipe Rolls of building at Dieulacres financed by Edward I or Edward III. Royal benefactions were not normally kept hidden under a bushel: if the Black Prince gave 500 marks to Dieulacres as well as to Vale Royal one would expect to find some first-hand evidence of it. The coincidence is really too remarkable to be acceptable, and one has to conclude, however regretfully, that Knighton mistook Dieulacres for Vale Royal, and that the church at Dieulacres was not rebuilt by its royal patrons.

Even if Dieulacres remained substantially as it had been left by Ranulph lII’s builders in the midthirteenth century, that is not to say that is was unimpressive. Ranulph was probably the wealthiest nobleman in England, and the legacy of his heart to be buried at Dieulacres is indicative of his great love for the abbey. The church in an abbey was the nerve-centre of monastic life, and in spite of the Cistercians’ early insistence on simplicity, their churches were among the grandest in the country. It was there that the monastic vocation was primarily fulfilled in the Opus Dei, the singing of the Divine Office, at which all the choir monks were required to be present. The twelve “hours” of the natural day varied in length according to the season of the year, but the same basic pattern of worship was maintained through summer and winter, punctuated by periods of manual work and study, the two other elements of monastic life.

Valuable information about the plan and dimensions of the church and conventual buildings at Dieulacres is contained in a letter which was published in Gentleman ’s Magazine (1819, part l). The correspondent was a Mr. J. A. Blackwell of Cobridge, Stoke-on-Trent, who apparently visited the site while it was being excavated in the Spring of the previous year. The excavation was a quarrying exercise, not an archaeological one, and Blackwell expresses a certain regret: “At this time no doubt a ground plan of the buildings might easily have been taken, which is not now possible, as many of the foundations have been pulled up to furnish materials for a range of cow-houses, stables, etc., that have been erected on the site of the abbey”. Part of the site was in fact very carefully measured and recorded. Both the 1862 and 1883 editions of John Sleigh’s History of the Ancient Parish of Leek contain a plan with very precise measurements of the height and thickness of the surviving columns and walls, and the dimensions of the various parts of the building. Whoever drew up the plan may not have been very familiar with monastic sites, for he made no attempt to interpret or label the features he recorded, but one is only grateful that a plan was made at all.

What the plan so obviously shows is the tower crossing, part of the presbytery, the south transept, and the eastern range of conventual buildings including the Chapter House (Plan 1). In his letter, Blackwell says that the church does not seem to have had any transepts, yet the plan shows, as one would expect, 'that there were transepts on the north and south sides. On the other hand, Blackwell mentions the bases of five columns lying to the west of the crossing, and these are not shown on the anonymous plan.

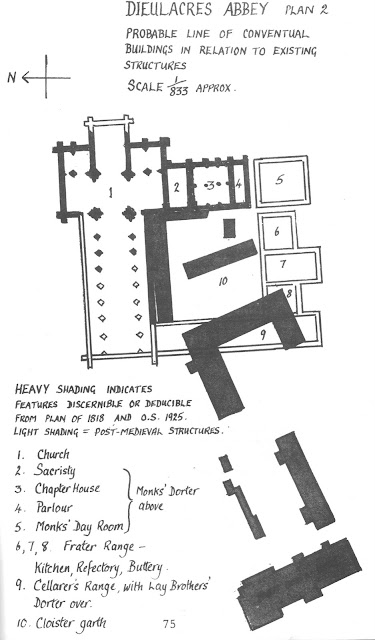

Using the report and plan of 1818, and modern O.S. maps, an attempt has been made to show the probable layout of the abbey in relation to the existing farm buildings (plan 2). One of these buildings runs approximately east-west, following the line of the church, and it could well incorporate the foundations of the south wall of the nave. To the east, and at right-angles to it, there is a length of wall which marks the line of the west side of the sacristy and Chapter House. The other 19th century buildings are differently aligned, a range of cow-sheds and an adjacent yard largely occupying the site of the cellarer’s buildings and laybrothers’ dormitory. The foundations of the southern range, including the frater, are only partially built over, and probably survive below ground. To the south, Abbey Farm contains a timber-framed archway (plate 3) which may have formed part of the abbey’s inner gateway.

A cattleroad runs down the centre of what was once the nave of the church, and this part of the site is nearly always wet owing to seepage from the slopes of Hillswood immediately to the north. lf anything survives of the nave wall and transept on the north side, it lies well buried, and therefore protected, behind the modern boundary fence. The base of one of the piers on this side was discernible prior to 1965. lt has since disappeared; so too has a column in the south transept which stood to a height of about six feet (plate 9).

From the plan of 1818 we can calculate that the eastern range of buildings extended about 100 feet south of the nave wall. Assuming that the cloister was more or less square, the nave of the church would have been of similar length, and though no reliable measurements are available,6 nave arcades of seven or eight bays would accord with the general Cistercian plan. The combined width of the nave and aisles seems to have been 63 feet. The monks’ choir would have occupied the two eastern bays, a stone screen., or pulpítum, separating it from the western part of the nave which was used by the lay-brethren. At the east end of the nave was the tower crossing. The bases of the piers on the south side have survived, one being ten feet in diameter. The crossing arches were unusually wide 129 feet and the tower above contained at least six bells. To the east, the presbytery would have extended no more than about 30 feet beyond the transepts, and it was almost certainly square ended. As all Cistercian churches were dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, there was no need for a separate Lady Chapel.

Valuable information about the plan and dimensions of the church and conventual buildings at Dieulacres is contained in a letter which was published in Gentleman ’s Magazine (1819, part l). The correspondent was a Mr. J. A. Blackwell of Cobridge, Stoke-on-Trent, who apparently visited the site while it was being excavated in the Spring of the previous year. The excavation was a quarrying exercise, not an archaeological one, and Blackwell expresses a certain regret: “At this time no doubt a ground plan of the buildings might easily have been taken, which is not now possible, as many of the foundations have been pulled up to furnish materials for a range of cow-houses, stables, etc., that have been erected on the site of the abbey”. Part of the site was in fact very carefully measured and recorded. Both the 1862 and 1883 editions of John Sleigh’s History of the Ancient Parish of Leek contain a plan with very precise measurements of the height and thickness of the surviving columns and walls, and the dimensions of the various parts of the building. Whoever drew up the plan may not have been very familiar with monastic sites, for he made no attempt to interpret or label the features he recorded, but one is only grateful that a plan was made at all.

What the plan so obviously shows is the tower crossing, part of the presbytery, the south transept, and the eastern range of conventual buildings including the Chapter House (Plan 1). In his letter, Blackwell says that the church does not seem to have had any transepts, yet the plan shows, as one would expect, 'that there were transepts on the north and south sides. On the other hand, Blackwell mentions the bases of five columns lying to the west of the crossing, and these are not shown on the anonymous plan.

Using the report and plan of 1818, and modern O.S. maps, an attempt has been made to show the probable layout of the abbey in relation to the existing farm buildings (plan 2). One of these buildings runs approximately east-west, following the line of the church, and it could well incorporate the foundations of the south wall of the nave. To the east, and at right-angles to it, there is a length of wall which marks the line of the west side of the sacristy and Chapter House. The other 19th century buildings are differently aligned, a range of cow-sheds and an adjacent yard largely occupying the site of the cellarer’s buildings and laybrothers’ dormitory. The foundations of the southern range, including the frater, are only partially built over, and probably survive below ground. To the south, Abbey Farm contains a timber-framed archway (plate 3) which may have formed part of the abbey’s inner gateway.

A cattleroad runs down the centre of what was once the nave of the church, and this part of the site is nearly always wet owing to seepage from the slopes of Hillswood immediately to the north. lf anything survives of the nave wall and transept on the north side, it lies well buried, and therefore protected, behind the modern boundary fence. The base of one of the piers on this side was discernible prior to 1965. lt has since disappeared; so too has a column in the south transept which stood to a height of about six feet (plate 9).

From the plan of 1818 we can calculate that the eastern range of buildings extended about 100 feet south of the nave wall. Assuming that the cloister was more or less square, the nave of the church would have been of similar length, and though no reliable measurements are available,6 nave arcades of seven or eight bays would accord with the general Cistercian plan. The combined width of the nave and aisles seems to have been 63 feet. The monks’ choir would have occupied the two eastern bays, a stone screen., or pulpítum, separating it from the western part of the nave which was used by the lay-brethren. At the east end of the nave was the tower crossing. The bases of the piers on the south side have survived, one being ten feet in diameter. The crossing arches were unusually wide 129 feet and the tower above contained at least six bells. To the east, the presbytery would have extended no more than about 30 feet beyond the transepts, and it was almost certainly square ended. As all Cistercian churches were dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, there was no need for a separate Lady Chapel.

In the south wall of the south transept the foot of the night stairs could still be seen in 1818. These gave direct access to the church from the monks’ dormitory above the Chapter House range. The name is a reminder that in the middle of the night the monks were roused from their slumbers to file silently down into the church for the singing of the Night Office. The transepts of Cistercian churches were usually divided, at their east end, into two or more chapels. In the twelfth century churches these chapels were normally separated from each other by solid walls, as for example at Bindon. Buildwas and Cleeve. This was less common in later foundations, and the transepts at Dieulacres, like those at Croxden, each had a pair of chapels divided only by a pillar and single arch, but with a solid wall screening both from the presbytery. A two-bay arcade divided the chapels from the rest of the transept, and the responds are clearly visible on the plan of 1818.

As to the furnishings of the church, the Dissolution records show that the Cistercians’ early insistence on simplicity was more or less strictly observed at Dieulacres right down to the sixteenth century. The high altar is described as a “fayre table of alerbaster”, and it was furnished with two large Candlesticks of base metal. There were eight more altars: provision had to be made for priestmonks to say their own Mass as well as attending the daily Conventual Mass. Four of these altars, would have been the transept chapels. The other four, made of alabaster, are described as beiiig in the aisles, and two of them would almost certainly have been against the western wall of the pulpitum or screen. In addition to the pulpitum, there would have been a rood-screen across the nave, and it seems as though this was of timber. It carried a large crucifix, and twelve Candlesticks of base metal. The only other items of furniture mentioned in the Dissolution records are a large lectern, the choir stalls, and an old lamp. [7] Gravestones are mentioned, and We have details of two of these. In the wall of one of the farm buildings there is a grave slab incised with a cross and sword, possibly from an abbot’s tomb (plate 4). The Dieulacres Chronicler not only refers to the burial of Ranulph III’s heart in the abbey church; he records the epitaph too:

"PRO DOLOR IN MURO IACET HIC SUB MARMORE DURO COR COMITIS CLAUSUM QUI CUNCTIS PRESTITIT AUSUM.

CHRISTE DEI FILI QUO CUNCTA CREANTUR IN YLI HOSTIA SACRA POLI RANULPHO CLAUDERE N0LI” [8]

An approximate translation is, “Alas, here in the wall, enclosed beneath hard marble, lies the heart of the Earl who exceeded all in daring. O Christ the Son of God, in whom all things have their being; Do not shut the sacred gates of heaven to Ranulph”. The cloister lay on the south side of the church. The Dissolution inventory indicates that the cloister-walks were roofed-in and glazed, and that they contained seats for the monks and a laver where they would wash after work and before taking their meals. The buildings on the east side of the cloister comprised the sacrisry, chapter house, parlour and monks’ dayroom. The vestry sacristy adjoined lïhe church, and it would probably have housed the abbey`s library as well as the vestments and altar vessels. Among the ítems as unsold in 1538 were 87 ounces of gilt plate consisting of three chaliees and the head of a cross-staff, and 30 ounces of silver, namely six spoons and plate taken from a wooden cross. There was an impressive collection of vestments and the founding fathers of the Cistercian Order would have clone more than raise an eyebrow at their richness. There were live High Mass sets consisting of chasuble, dalmatic and tunicle, and presumably matching stoles and maniples, Four of the sets had matching copes too. There were four other capes, one figured with a nativity scene on the hood, four assorted haubles and four tunicles. Some of these vestments were made of embroidered silk, and some of “baudekyn” which was most, expensive of all ecclesiastical fabrics, a kind of heavy silken brocade, often interwoven with gold and silver thread. Nevertheless, the entire collection was sold for as little as £3.

Next to the sacristy was the chapter house, so called because of the ancient practice of beginning the daily meeting of the community with the reading of a chapter from the Rule of St. Benedict. The chapter house at Dieulacres was thirty feet square, the roof being supported by a pair of free-standing columns, matching engaged columns along the walls and quarter-shafts in the comers. This suggests quadripartite stone vaulting above, and the chapter house would have been an impressive and aesthetically pleasing room. Adjoining the chapter house was an oblong room measuring 30ft by Comparison with other Cistercian plans shows that this would have been the parlour (from the French parler, to talk), Where necessary conversation was aliowed: discussions between the abbot and his officials; day-to-day administratioii ofthe monastery and its estates. more is shown on the pian, and Blackwell’s letter contains only a general statement that “on the south side (of the church) the foundations of several of the offices of the monastery may be discerned”. Comparative plans suggest that next to the parlour a narrow passageway or “slype” would have given access from the cloister to the infermary (“farmery") buildings on ihe south east side of the main complex. South of the slype, the eastern range wouid have terminated in the monks’ common room or day room which contained the only fireplace accessible to the brethren in the cold winter months. At first-floor level the monks’ dorter, or dormitory, ran the whole length of the eastern range. The Dissolution inventory mentions “oulde desks" in the dorter, which suggests that it may have been used for writing and study as well as for sìeeping. The fact that no beds are mentioned has been taken by some as an indication that by 1538 the monks had abandoned their communal dormitory in favour of the more comfortabie private chambers referred to elsewhere in the inventory. [9] but this is not so, The inventory is concerned only with goods that were actually sold. There is no mention of any furniture in the infirmary yet there surely must have been some, ln any case, there were only four private rooms, hardly sufficient to accommodate thirteen monks.

The Commissioners seem to have toured the monastic buildings in a clockwise direction: first the church, then the sacristy, chapter house and dorter. If for “frater” we read “common room" then there is a logical progression from there to the “farmery” (infirmary) and back to the buildings on the south side of the cloister, namely the frater range. In most Cistercian monasteries the frater, or monks’ refectory, was built at right angles to the line of the range, projecting southwards beyond the adjacent kitchens and other domestic rooms. Sometimes, as for example at Cleeve, the frater was at level, with a number of private chambers below, and one wonders whether this may have been the case at Dieulacres. What the inventory describes as the “hall” was presumably the frater itself, for it contained tables and forms such as one would expect to find in a communal dining room. The adjoining buttery, larder, kitchen and "poultyinghouse” contained an interesting assortment of hardware: “great brass pottes" and “choppyng-knives”, “ehafyngdyshys” and "hoggesheads”, while the mention of a brewhouse is a reminder that medieval monasteries produced their own ale.

The four private chambers which appear to have been situated in the frater range are listed as the Corner Chamber, the Riders’ Chamber, the Butler`s Chamber and the Labourers’ Chamber. They were quite elaborately furnished, and some of the names suggest use by officials of the abbey. As we know from the history of Dieulacres, corrodians were lodged there, and visiting officials from remote parts of the estates, e.g. Richard Grosvenor, Steward of Poulton, and John Alen, Bailiff of the Lancashire manors, would also have needed accommodation from time to time. No mention is made in the inventory of the cellarer’s range, which would have occupied the western side of the cloister, nor of the laybrothers’ dormitory above it. The latter would have long ceased to be used for its original purpose, as the laybrethren had largely disappeared from the Cistercian system by the end of the fourteenth century.

So much of this attempted reconstruction is conjectural, yet there is no reason to suppose that Dieulacres was greatly different from the many Cistercian abbeys for which detailed plans are available. Only an archaeological excavation could help to in the gaps, and even then one would expect to find little more than foundations and footings.

No account of the abbey buildings would be complete without reference to St. Edward’s Church, Leek, of which the abbot and monks of Dieulacres were patrons for over 300 years. St. Edward’s has many curious architectural features, not least of which are the wheel windows in the north and south aisles, which Pevsner describes as “a typical Decorated conceit”. [10] We know from the Chronicle of Croxden Abbey that the church and town of Leek were accidentally burned down on the night of June 10th, 1297. [11] The rebuilding of the church was no doubt undertaken by the abbot’s clerk of works and masons, and the wheel windows may well have been a piece of extravagance on the part of Abbot Robert Burgilon (c. 1292-1302). They are of the kind that one would expect to see in the transept gables of an abbey or cathedral, and it is at least conceivable that they are copies of windows in the church at Dieulacres. They are not now in their original situation, at least the one on the north side is certainly not. Writing in the 1730s, Thomas Loxdale refers to the "abbot’s chapel”, with a carved "railing" or screen on its south side, presumably to partition it from the rest of the church, and the coat-of-arms of one of the abbots was visible in the carving.“ On a map of Leek drawn in 1838, [13] St. Edward’s is shown as having a transept like projection at the north-east corner of the north aisle, juast where the wheel window now one is tempted to the conclusion that this was the abbots chapel mentioned by Loxdale, and it would aîmoet eertainìy have contained one if not both of the wheel windows, the whoìe chapel being ai visible reminder to the parishioners of Leek of who their spiritual overlord was. lt was demolished during a major reorganisation of St. Edward’s in 1838, but it is pleasant to think that in the resited wheel windows and possibly in the ambitious east window of the Lady Chapel too, there may be an echo of the great abbey which lay across the Churnet valley. [14]

Go to - Chapter 9

As to the furnishings of the church, the Dissolution records show that the Cistercians’ early insistence on simplicity was more or less strictly observed at Dieulacres right down to the sixteenth century. The high altar is described as a “fayre table of alerbaster”, and it was furnished with two large Candlesticks of base metal. There were eight more altars: provision had to be made for priestmonks to say their own Mass as well as attending the daily Conventual Mass. Four of these altars, would have been the transept chapels. The other four, made of alabaster, are described as beiiig in the aisles, and two of them would almost certainly have been against the western wall of the pulpitum or screen. In addition to the pulpitum, there would have been a rood-screen across the nave, and it seems as though this was of timber. It carried a large crucifix, and twelve Candlesticks of base metal. The only other items of furniture mentioned in the Dissolution records are a large lectern, the choir stalls, and an old lamp. [7] Gravestones are mentioned, and We have details of two of these. In the wall of one of the farm buildings there is a grave slab incised with a cross and sword, possibly from an abbot’s tomb (plate 4). The Dieulacres Chronicler not only refers to the burial of Ranulph III’s heart in the abbey church; he records the epitaph too:

"PRO DOLOR IN MURO IACET HIC SUB MARMORE DURO COR COMITIS CLAUSUM QUI CUNCTIS PRESTITIT AUSUM.

CHRISTE DEI FILI QUO CUNCTA CREANTUR IN YLI HOSTIA SACRA POLI RANULPHO CLAUDERE N0LI” [8]

An approximate translation is, “Alas, here in the wall, enclosed beneath hard marble, lies the heart of the Earl who exceeded all in daring. O Christ the Son of God, in whom all things have their being; Do not shut the sacred gates of heaven to Ranulph”. The cloister lay on the south side of the church. The Dissolution inventory indicates that the cloister-walks were roofed-in and glazed, and that they contained seats for the monks and a laver where they would wash after work and before taking their meals. The buildings on the east side of the cloister comprised the sacrisry, chapter house, parlour and monks’ dayroom. The vestry sacristy adjoined lïhe church, and it would probably have housed the abbey`s library as well as the vestments and altar vessels. Among the ítems as unsold in 1538 were 87 ounces of gilt plate consisting of three chaliees and the head of a cross-staff, and 30 ounces of silver, namely six spoons and plate taken from a wooden cross. There was an impressive collection of vestments and the founding fathers of the Cistercian Order would have clone more than raise an eyebrow at their richness. There were live High Mass sets consisting of chasuble, dalmatic and tunicle, and presumably matching stoles and maniples, Four of the sets had matching copes too. There were four other capes, one figured with a nativity scene on the hood, four assorted haubles and four tunicles. Some of these vestments were made of embroidered silk, and some of “baudekyn” which was most, expensive of all ecclesiastical fabrics, a kind of heavy silken brocade, often interwoven with gold and silver thread. Nevertheless, the entire collection was sold for as little as £3.

Next to the sacristy was the chapter house, so called because of the ancient practice of beginning the daily meeting of the community with the reading of a chapter from the Rule of St. Benedict. The chapter house at Dieulacres was thirty feet square, the roof being supported by a pair of free-standing columns, matching engaged columns along the walls and quarter-shafts in the comers. This suggests quadripartite stone vaulting above, and the chapter house would have been an impressive and aesthetically pleasing room. Adjoining the chapter house was an oblong room measuring 30ft by Comparison with other Cistercian plans shows that this would have been the parlour (from the French parler, to talk), Where necessary conversation was aliowed: discussions between the abbot and his officials; day-to-day administratioii ofthe monastery and its estates. more is shown on the pian, and Blackwell’s letter contains only a general statement that “on the south side (of the church) the foundations of several of the offices of the monastery may be discerned”. Comparative plans suggest that next to the parlour a narrow passageway or “slype” would have given access from the cloister to the infermary (“farmery") buildings on ihe south east side of the main complex. South of the slype, the eastern range wouid have terminated in the monks’ common room or day room which contained the only fireplace accessible to the brethren in the cold winter months. At first-floor level the monks’ dorter, or dormitory, ran the whole length of the eastern range. The Dissolution inventory mentions “oulde desks" in the dorter, which suggests that it may have been used for writing and study as well as for sìeeping. The fact that no beds are mentioned has been taken by some as an indication that by 1538 the monks had abandoned their communal dormitory in favour of the more comfortabie private chambers referred to elsewhere in the inventory. [9] but this is not so, The inventory is concerned only with goods that were actually sold. There is no mention of any furniture in the infirmary yet there surely must have been some, ln any case, there were only four private rooms, hardly sufficient to accommodate thirteen monks.

The Commissioners seem to have toured the monastic buildings in a clockwise direction: first the church, then the sacristy, chapter house and dorter. If for “frater” we read “common room" then there is a logical progression from there to the “farmery” (infirmary) and back to the buildings on the south side of the cloister, namely the frater range. In most Cistercian monasteries the frater, or monks’ refectory, was built at right angles to the line of the range, projecting southwards beyond the adjacent kitchens and other domestic rooms. Sometimes, as for example at Cleeve, the frater was at level, with a number of private chambers below, and one wonders whether this may have been the case at Dieulacres. What the inventory describes as the “hall” was presumably the frater itself, for it contained tables and forms such as one would expect to find in a communal dining room. The adjoining buttery, larder, kitchen and "poultyinghouse” contained an interesting assortment of hardware: “great brass pottes" and “choppyng-knives”, “ehafyngdyshys” and "hoggesheads”, while the mention of a brewhouse is a reminder that medieval monasteries produced their own ale.

The four private chambers which appear to have been situated in the frater range are listed as the Corner Chamber, the Riders’ Chamber, the Butler`s Chamber and the Labourers’ Chamber. They were quite elaborately furnished, and some of the names suggest use by officials of the abbey. As we know from the history of Dieulacres, corrodians were lodged there, and visiting officials from remote parts of the estates, e.g. Richard Grosvenor, Steward of Poulton, and John Alen, Bailiff of the Lancashire manors, would also have needed accommodation from time to time. No mention is made in the inventory of the cellarer’s range, which would have occupied the western side of the cloister, nor of the laybrothers’ dormitory above it. The latter would have long ceased to be used for its original purpose, as the laybrethren had largely disappeared from the Cistercian system by the end of the fourteenth century.

So much of this attempted reconstruction is conjectural, yet there is no reason to suppose that Dieulacres was greatly different from the many Cistercian abbeys for which detailed plans are available. Only an archaeological excavation could help to in the gaps, and even then one would expect to find little more than foundations and footings.

No account of the abbey buildings would be complete without reference to St. Edward’s Church, Leek, of which the abbot and monks of Dieulacres were patrons for over 300 years. St. Edward’s has many curious architectural features, not least of which are the wheel windows in the north and south aisles, which Pevsner describes as “a typical Decorated conceit”. [10] We know from the Chronicle of Croxden Abbey that the church and town of Leek were accidentally burned down on the night of June 10th, 1297. [11] The rebuilding of the church was no doubt undertaken by the abbot’s clerk of works and masons, and the wheel windows may well have been a piece of extravagance on the part of Abbot Robert Burgilon (c. 1292-1302). They are of the kind that one would expect to see in the transept gables of an abbey or cathedral, and it is at least conceivable that they are copies of windows in the church at Dieulacres. They are not now in their original situation, at least the one on the north side is certainly not. Writing in the 1730s, Thomas Loxdale refers to the "abbot’s chapel”, with a carved "railing" or screen on its south side, presumably to partition it from the rest of the church, and the coat-of-arms of one of the abbots was visible in the carving.“ On a map of Leek drawn in 1838, [13] St. Edward’s is shown as having a transept like projection at the north-east corner of the north aisle, juast where the wheel window now one is tempted to the conclusion that this was the abbots chapel mentioned by Loxdale, and it would aîmoet eertainìy have contained one if not both of the wheel windows, the whoìe chapel being ai visible reminder to the parishioners of Leek of who their spiritual overlord was. lt was demolished during a major reorganisation of St. Edward’s in 1838, but it is pleasant to think that in the resited wheel windows and possibly in the ambitious east window of the Lady Chapel too, there may be an echo of the great abbey which lay across the Churnet valley. [14]

Go to - Chapter 9

Dieulacres Abbey Posted at 11:50 |

0 comments

0 Comments: